Power struggles are a normal part of growing up, for kids and for parents. But for children with disabilities, there is a lot at risk if parents don’t learn effective ways to minimize power struggles.

Adults with disabilities may always need some sort of guidance, support, and supervision to be healthy, safe, and independent people.

If families struggle with communication, choice, and control when a child is young, I have seen that these challenges only become more intense as the child becomes an adult. Many of my counseling clients who are parents raising kids with disabilities talk about power struggles as an immediate source of stress and anxiety.

This is when power struggles become truly dangerous, as an adult who is angry and feels that they lack control can seriously harm themselves and others.

That’s why I think it’s critical that parents of kids with disabilities make it a goal from a very young age to give their child as much independence and choice as it is safe for them to have.

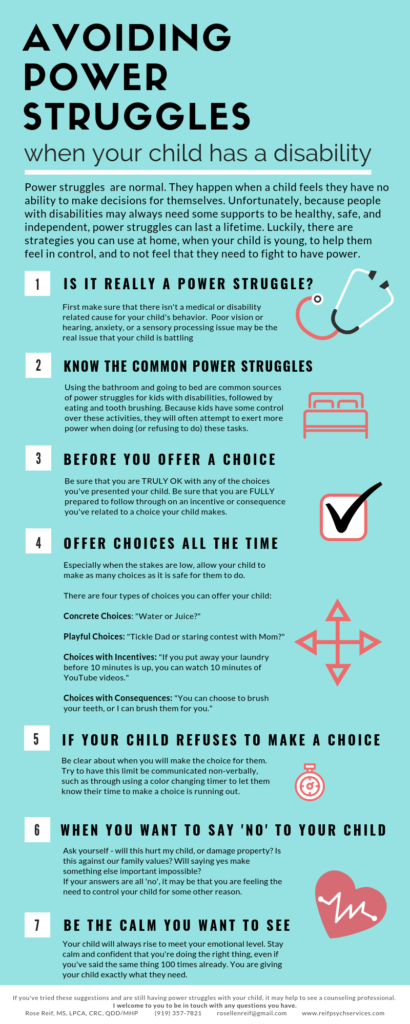

Is it really a power struggle?

Before trying any of the techniques outlined here, think about the common power struggles that play out in your house.

If the sources of power struggles are truly baffling to you, consider if there may be some medical or other factor at play.

If your child resists and engages in a battle whenever its time to get dressed, maybe they have a sensory need that’s not being met by their clothes (such as needing to feel ‘hugged’ by their shirts).

Perhaps your child’s left ear is clogged with wax and he can’t hear your requests, and he’s simply responding with frustration because he senses your agitation when you ask him to do something for the fifth time.

If any of your family’s common power struggles might be better explained by medical or disability related need that your child can’t express, look into resolving those root causes before trying any of the strategies outlined below.

Common Power struggles for Kids with Disabilities

For children and adults with disabilities, the need to feel in control is very real. There are often few things that they genuinely have control over. When to wake, what to eat, where to work, and who to live with are all choices that people with disabilities don’t often get to fully make for themselves.

Using the bathroom and choosing when to fall asleep are the two things that a child with a disability may have the most control over; not surprisingly, toileting and bedtime are a source of frequent power struggles in many families affected by disability.

The next most common sources of power struggles for kids with disabilities are things that a parent could conceivably ‘make’ a child do, but that it would be very difficult to follow through on, like eating and tooth brushing. Again, the child recognizes the relative control they have in these situations, and tries to exert even more power, to compensate for other areas where they have little or no say in what happens to them.

How do you prevent power struggles before they start?

Offer choices, especially when the stakes are low.

Every time you offer a choice, you give your child power. Every time your child is given power, they feel less need to fight for power.

There are two things you must be:

- Ok with all choices you’re offering – don’t say we can go to the library or go to the pool if you’re not REALLY prepared to pack your beach bag and head to the pool. It doesn’t matter if your child has asked to go to the library every day for the last two years; there will come a day when they will want to do something different, and you must be prepared to do what you’ve offered as choices.

- Ready to follow through on any outcomes – if you state that there is a consequence or reward associated with a choice, you must be 100% ready to follow through on this.

Do not promise Disney World if you cannot be walking down Main Street, USA towards Cinderella’s Castle at the time you’ve promised.

Even if you think there’s no way your child will make the ‘correct’ choice and earn the reward, there will come a day when they will surprise you.

If you can’t follow through on your promises, you set yourself up as untrustworthy. This will only cause your child to feel less in control. If they don’t view their parent as capable of following through on promises, this will set you up for more future power struggles.

The Four Types of Choices

Now that you’re truly ready to offer choices, you have some choices!

Concrete Choices:

“Do you want water or juice to drink with your snack?”

These are often low stakes choices. For a child who compulsively prefers one food/song/T-shirt, this can be a great option to ‘break the cycle’. Remove the preferred item from sight, and then offer two alternatives. If they ask for something that you haven’t offered as a choice? Stick to your guns and your script. Keep calmly reiterating what options they have.

Playful Choices:

“Do you want to wear your pajamas or your Spiderman costume to the bank?”, “Do you want to tickle Dad or have a staring contest with Mom?”

These are really just concrete choices, but the element of whimsy and fun make them something more for kids. You are allowing them to slightly break with convention and rules, and to not only make their own choice, but to do something a little outrageous. Kids with disabilities feel tremendous power when given playful choices. Try to offer at least one playful choice per day to your child with disabilities.

Choices with Incentives:

“If you put away all of your clean laundry before 10 minutes is up, you can watch 10 minutes of YouTube videos.”

I usually recommend to my counseling clients that they be as non-verbal as possible in following through on these types of choices. So, don’t tell your child when 10 minutes has passed, just use a color countdown timer, like this one. This takes away YOUR power in the situation. It is now your child against the clock, and not your child against you.

Choices with Consequences:

“You can choose to brush your teeth, or I can brush them for you.”

As with incentivized choices, try to make this as non-verbal as possible. Using a picture schedule or reward chart, and pointing to it silently, are great ways to deflect your child’s frustration from building against you. Instead, it becomes a matter of them following through on a agreement they’d already bought into.

Using routine and choice to avoid power struggles

If your child is always begging for “just one more book” at bedtime, then establish some new parameters; every night you will read them three books. They may choose whichever three books they’d like, but you won’t read more or less than three.

The trick here, of course, is sticking to the routine as a parent when life gets in the way. Rather than try to deflect that the bedtime routine tonight is slightly different, and hope your child won’t notice, it is typically better to tell your child why the routine will need to change, offering the opportunity for more choice if possible.

“I’m sorry that I can’t read you three books tonight. I have to go to a meeting tonight during your bedtime, so, I won’t be at home to read three books with you. Your babysitter can read three books that you choose with you, or I can read you one book in the morning before breakfast. Which would you like?”

What if your child refuses to make a choice?

Be clear about when you will make the choice for them, using a non-verbal cue if possible. Whether it’s at a certain time, or when something happens (such as when Dad gets home), set a limit on how long your child has to make their choice, and clearly let them know that if they haven’t made a choice by then, you will be making a choice for them.

Try to reserve this for instances when it really is critical, such as needing to choose a shirt to wear to leave the house for school.

If it’s a non-critical issue, try to allow your child to experience the natural consequences of their refusal to make a choice (again, making sure beforehand that you’re ok with how that might play out). Maybe your child won’t decide between water and juice because they want soda, but you have a no sodas with dinner rule. Unless there’s a medical reason why you can’t, simply don’t provide them with a drink until they make a choice.

Inevitably, your child will say they’re thirsty. Using as non-judgmental a tone as you can muster, say “I imagine that’s because you didn’t choose a drink”. Your goal is to make the observation that your child’s refusal to make a choice caused their discomfort, whatever that might be.

When your child with a disability asks to do something, and you want to say ‘No’

Kind of like the improv theater game, I find it can be really helpful if you always respond “Yes, and…”

So, if it’s a rainy day and your child asks to go to the playground you might say “Yes, and I wish we could do that, too. The trouble is that it’s raining and that makes it yucky and messy to play at the playground. Should we go to the inside playground at the mall instead?”

Of course, there will always be times when your answer is still ‘No’. At these times, ask yourself, will saying yes:

- hurt my child?

- damage property?

- be at odds with our family’s values or rules?

- prevent something else important from happening (such as getting to school on time)?

If the answer to all of these is ‘No’, but you still feel the urge to say ‘No’ to your child, it may help to reflect on what’s going on internally with you.

Maybe you are tired or sick. Perhaps you resent that your spouse isn’t the one who your child engages in power struggles. If you’re feeling powerless because of a burden you’re facing, you may be trying to feel more ‘in control’ by exerting control over your child.

Before you beat yourself up over this, accept that it is human nature to want to have control over something. Recognize that you have done a difficult thing in spotting this desire for power in yourself. Consider what your true needs are, and if there’s another way you could or should be meeting them.

Always be the calm you want to see

Speaking louder, holding tighter, or otherwise allowing frustration to take hold of you, the parent, is setting the stage for a power struggle. Your child will always, in some way, rise to meet your emotional level, no matter what their cognitive or communication abilities are.

It is difficult in the beginning. You may need to repeat choices a hundred times before your child with a disability sees that they cannot choose to wear the dirty t-shirt they’ve worn for three straight days today, that they must pick another.

Over time, though, your child will come to see that you are calm, kind, but firm. They will stop viewing you as being at odds with them, and they will see instead that you offer them structure and choice, while at the same time keeping them safe. They will see that you are always consistent.

This is what all kids, regardless of their age and whether or not they have a disability, truly crave from their parents. Calm and consistency.

If you find that you and your child with disabilities are still frequently stuck in power struggles, it may be helpful to get some outside perspective. Invite a counselor to meet with you for a session or to come to your home for a family observation, to see if there are small changes you could make in your routine to offer your child more choice, and more sense of control in their lives.

If this post was helpful to you, please click the social buttons and share it with others!