What my counseling clients with Intellectual Disabilities tell me about learning to ‘breathe deep’

Usually my counseling clients with intellectual disabilities have been coached in deep breathing in the past. When I ask them about it, the answer is usually “yeah…that didn’t go so well.”

They will typically describe that someone encouraged them to ‘clear their mind’ and to ‘take big deep breaths’.

But these instructions are abstract and vague. Most people with ID thrive when communication is concrete, literal, and presented visually. Because these instructions weren’t clear, they caused more anxiety for the person with ID. So, in addition to the pain or worry or , the person was left feeling inadequate and anxious.

Most of my clients initially refuse to show me how they ‘breathe deeply’. Because their past experiences being coached in breathing were so terrible, they’re afraid to try again.

Thankfully, all of them to date have allowed me to use some workaround techniques to help them benefit from deep breathing. Ultimately, this has given them confidence in their ability to effectively use these skills to calm themselves. I love teaching my clients to manage pain or anxiety through diaphragmatic breathing, and here’s how I do it.

These two simple processes can be used together or independently to teach deep breathing to people with intellectual disabilities. All you’ll need is:

- a hand (yours or the hand of the person you’re coaching)

- a small, lightweight, flat object (plates and small hardcover books are perfect for this).

TECHNIQUE # 1 – Smell your favorite smell, then blow out the candle

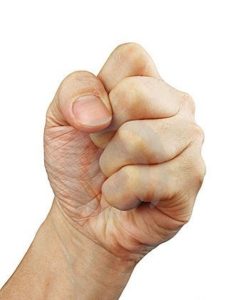

First, show the person your hand as a fist.

Explain that you want them to imagine that your fist is something that smells wonderful. You can assign an imaginary smell to the fist. But for most people, this will be more meaningful if they imagine their own favorite smell.

I’ve had clients say that the fist is lemons, a cup of broccoli cheese soup, a chocolate bar, their favorite perfume, and so on.

Doesn’t matter what it is, as long as it’s a smell they love and that has generally positive associations for them.

For instance, I once had a client say she loved the smell of orchids. But, she said that the smell also reminded her of her grandmother’s funeral. It wouldn’t have been wise for her to use that smell for this exercise. Even though she found the smell pleasant, it reminded her of something that made her feel sad and anxious.

Tell the person you’re coaching that when they see your fist they should image that favorite smell. Coach them to breath in deeply to try to smell as much of it as possible.

Now, show the person your hand with your index finger raised.

Tell them that your hand like this is a candle that they need to blow out. When they see your hand with your index finger up, they should blow out the candle until it’s all the way out.

Practice each skill, inhaling and exhaling, independently. Do this until the person is consistently able to do each without prompting (verbal or visual based on their communication needs).

Then, combine the skills, so that they first inhale their “favorite smell”, and then blow out the candle. Because your hand is in control, you can gradually increase the length of time that each breathing cycle lasts. This is important to help ‘shallow breathers’ who are actually prone to overbreathing and hyperventilating!

Once the person with ID is able to do this exercise without any instruction, they can begin using their own hand and doing the exercise themselves.

Variation

Some clients who require a little more sensory feedback and involvement. For them, I will start by holding their ‘favorite smell’ item in one hand (such as a sprig of rosemary). Then, I’ll either hold a lit candle or a cigarette lighter in my other hand. For a while, we practice using these real items. Once they learn the mechanics of inhaling and exhaling using real objects, we move on to simply imagining that they are there as outlined above.

If an additional step is needed in between, I might hold a printed picture of the “favorite smell” item and of a candle to accomplish this. As they becoming increasingly capable of doing the exercise, it can also be helpful to first remove just one object (usually the candle can be the first to go), before taking both items away from the exercise.

If a client would be confused or overly stimulated by the sensory aspect of imagining a smell, I will sometimes hold a piece of paper so that it hangs in front of their face, and then coach them in inhaling and exhaling so that the piece of paper moves as they breathe.

What I don’t love about this variation is that there’s not as much reward for the inhalation, because a piece of paper won’t pivot as much from its equilibrium when you inhale as when you exhale.

I’m embarrassed to share how many weights and sizes of paper I have tested over the years to be able to say that with assurance.

let’s just say trust me on this one!

Yes, I could adjust my grip on the paper so that it would move inward as the client inhales, so that they are equally reinforced for inhaling as for exhaling. I don’t, because if my client tries to use this technique on their own, they won’t get the same feedback for their breathing, and I wouldn’t want them to think they’re ‘doing it wrong’.

It depends on the client, but usually I show them how even if I inhale very deeply, the piece of paper won’t move as much as it will when I exhale.

TECHNIQUE # 2 – Make the Plate Move

If you find that the person with ID continues to ‘heave’ with their chest rather than taking deep breaths using their diaphragm muscle, it’s time to incorporate the book or plate (or any small, lightweight, firm, flat object). If the person will tolerate lying down, that’s best for this technique, but read on to the variation if they won’t.

Once the person is lying down, place the item on their belly. Hold your hand in the air about an inch and a half above their belly. Remind them to keep their shoulders and buttocks on the floor. Then ask them to use their belly to make the plate touch your hand. Once they are able to do this, you can begin incorporating counting during inhalation and exhalation to teach them to take measured, slow breaths.

Variation

If the person won’t or can’t lie down for this exercise, you can accomplish the same thing sitting. I’ve also used the sitting variation when counseling people with pseudoseizures. I do this because often times lying down when they are feeling anxious may lead to a pseudoseizure. I want to teach my clients to do the breathing exercises as they will need to do them in actual times of anxiety or pain.

In this variation, you hold the plate an inch to an inch and a half in front of the person’s belly when they’re seated or standing. Then ask them to breathe using their belly muscles so that their belly touches the plate. Then simply follow the same process of adding counting as described above.

When to practice deep breathing

How often should someone with ID practice deep breathing

For deep breathing to be effective for someone, it’s essential that they practice routinely. They should also practice at times when they aren’t feeling stressed or in pain. That way, the mechanics of breathing become second nature to them. Only then will deep breathing be helpful when the person is in distress.

For someone with ID, it may take weeks or even months of daily practice for the mechanical aspects of diaphragmatic breathing to become second nature to them. Allow them this time!

Encourage them to be patient and persistent in practicing breathing, and help them use alternative calming strategies until they are truly confident in their ability to use deep breathing to manage their distress; trying to push them to calm themselves in this way before they trust that it will work for them can be really detrimental, and cause them to not want to use these techniques at all.

These exercises are best practiced three times per day, for 3-4 minutes at a time.

When in the day should someone with ID practice deep breathing

Because of I recommend around 3 practice sessions a day, many people think that it’ll be good to do breathing exercise before a meal. Their assumption is udnerstandable; the mealtime can serve as a trigger to remind them to practice

For most of my clients, however, the time just before meals can be a source of great anxiety. Because of this I usually expressly recommend that they don’t time breathing practice so that it immediately precedes mealtime. I find that doing so could cause an unintended association. They may mentally linking the anxiety that occurs just before mealtime with the breathing exercises (not good!).

Similarly, I don’t recommend that clients do breathing exercises just before a highly desired activity. They may try to rush through the breathing exercise to get to what’s on the other side.

Instead, I recommend that people with ID do breathing exercises just before doing an activity that they feel neutrally about. I find that this is more crucial than spacing the practices equally throughout the day. That means that if it makes sense in the schedule of a person with ID to do all of their daily breathing exercises before noon, because that’s when they do activities that they feel neutrally about, then that’s what will be most effective for them.

If this post has been helpful to you, please use the social share buttons to share it with others!